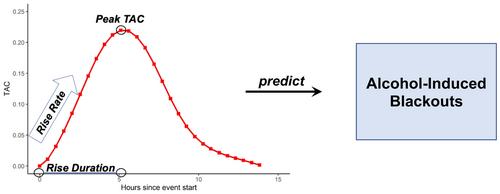

Alcohol-induced blackouts (AIBs) are common in college students. Individuals with AIBs also experience acute and chronic alcohol-related consequences. Research suggests that how students drink is an important predictor of AIBs. We used transdermal alcohol concentration (TAC) sensors to measure biomarkers of increasing alcohol intoxication (rise rate, peak, and rise duration) in a sample of college students. We hypothesized that the TAC biomarkers would be positively associated with AIBs.

Students were eligible to participate if they were aged 18–22 years, in their second or third year of college, reported drinking 4+ drinks on a typical Friday or Saturday, experienced ≥1 AIB in the past semester, owned an iPhone, and were willing to wear a sensor for 3 days each weekend. Students (N = 79, 55.7% female, 86.1% White, Mage = 20.1) wore TAC sensors and completed daily diaries over four consecutive weekends (89.9% completion rate). AIBs were assessed using the Alcohol-Induced Blackout Measure-2. Logistic multilevel models were conducted to test for main effects.

Days with faster TAC rise rates (OR = 2.69, 95% CI: 1.56, 5.90), higher peak TACs (OR = 2.93, 95% CI: 1.64, 7.11), and longer rise TAC durations (OR = 4.16, 95% CI: 2.08, 10.62) were associated with greater odds of experiencing an AIB.

In a sample of "risky" drinking college students, three TAC drinking features identified as being related to rising intoxication independently predicted the risk for daily AIBs. Our findings suggest that considering how an individual drinks (assessed using TAC biomarkers), rather than quantity alone, is important for assessing risk and has implications for efforts to reduce risk. Not only is speed of intoxication important for predicting AIBs, but the height of the peak intoxication and the time spent reaching the peak are important predictors, each with different implications for prevention.